After the introduction of Montessori’s First Great Lesson: The Coming of the Universe, lower elementary children are eager to explore The Second Great Lesson: The Coming of the Earth. This study of the Earth begins, as the Universe study began, with cultural origin stories from around the world, as well as the evolving story of the scientists which involves facts, evidence, and the Scientific Method. It incorporates physics, chemistry, geology, and physical geography. Children learn about the conditions which existed that allowed land to solidify and water to form in the first place.

As

in the Montessori 3-6 classroom, land and water forms are introduced in the 6-9

environment with greater detail and sophistication, and with different

materials. In the 3-6 environment, children often pour water into shaped land

forms to demonstrate land and water forms as opposites. For example, an island – which is land

surrounded by water – is the opposite of a lake – which is water surrounded by

land. This holds for the many other land and water forms studied in greater depth at the

6-9 level, such as isthmus and strait, cape and peninsula, etc.

Children

are introduced to plate tectonics and discover how land forms (which we call

continents) have been changing and moving on top of the crust of this planet

for billions of years. This study helps us to discuss the eternal situation on

this planet of climate change, which is affecting us as humans with great importance. Over the years, I have used various food items

to demonstrate the three kinds of plate boundaries – transforming, convergent,

and divergent. (This nomenclature also connects to terminology used in geometry

lessons for some of the children, further deepening their neural pathways.)

Whether I’ve used molasses, marshmallow fluff, or maple syrup with graham crackers,

the learning environment smells sweet for several days. Children enjoy the

texture of real materials as symbols of giant planetary processes.

The

study of geology continues with the factors that allowed for plate tectonic

activity – volcanoes and earthquakes. At the 6-9 level, children enjoy making

their own exploding volcanoes (using baking soda, vinegar, and food coloring)

and research famous eruptions to see how these natural disasters later affected

animal and plant lives.

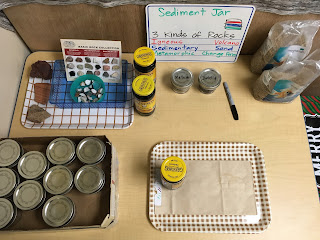

Long

before the first life forms existed, rocks did, and children learn about the

three main kinds: sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic. Real examples of these

rocks sit on our geology shelves waiting to be touched and understood. This

photo shows an extension that involves creating a sedimentation jar, revealing

the layers that these rocks make underneath our feet!

As

with land and water forms, the continent puzzle map cabinet is introduced in

Montessori 3-6 classrooms and used with more depth and detail at the 6-9 level.

Children make their own maps of the continents, which provides both a

direct aim (identifying land forms and water forms by name and shape) and many indirect aims: refining fine motor skill, connecting the child with places of

relative distance, and conceptualizing the spiritual aspect of self in relation to

land and water forms of such sizes and at such distances from one another.

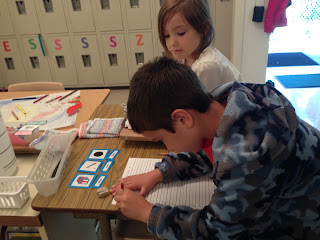

The

main purpose of the continent puzzle maps is not that a child will memorize all

of the names and locations of countries in Asia, but that s/he begins to grasp

his/her smallness within the infinite Universe, in terms of space, size, and

time. Children often share the labor of this work with a friend and ask the other to hand

him/her a certain country so that it may be traced, then labeled, then colored,

then brought home to wallpaper one’s bedroom.

Finally,

children continue learning about the Work of Wind and the Work of Water by

studying the atmosphere, erosion, and weather. A fun way to explore these

topics is to learn how to discriminate visually between different

kinds of clouds, their shapes, and their meanings when seen above us. Some

clouds portend rainy weather, others clear skies, and still others tell us

humans on the ground what speed and motion the wind is taking 25,000 feet up in the sky. These photos demonstrate secondary extensions children make after first studying

the three- or four-part cloud card materials.

These hands-on activities both serve the

multiple intelligences of different kinds of learners and ingrain the geographical concepts so that (just as with rocks and land and water forms) children make

connections in nature or on trips with their families, as well as within a

learning environment inside a building. After learning these initial concepts

with the concrete Montessori materials, any location transforms into a

classroom of the mind!