“To assist a child

we must provide him with an environment which will enable him to develop

freely.” – Maria Montessori

One of the most unique aspects of a

Montessori learning environment which sets it completely apart from other

classrooms is the preparation and sequencing of the materials which Maria

Montessori created over a century ago with the children whom she guided. Since

her death in 1952, Montessori guides (teachers) have continued using Montessori

materials and creating materials inspired by her scientific approach. In her

books, Montessori speaks so often about the importance of the prepared

environment where child can cultivate confidence, independence, and mastery.

“The environment

itself will teach the child, if every error he makes is manifest to him,

without the intervention of a parent or teacher, who should remain a quiet

observer of all that happens.” – Maria Montessori

Usually, shelves in the Lower

Elementary room are arranged by curricular area – Language, Math, Practical

Life, and Cultural studies. Guides rotate the shelves throughout a school year,

due in large part to the observations of the children by the adult guide. She

notices which materials are relevant and enticing to the children, and she also

observes when the children are no longer intrigued. When new materials appear,

interest is stirred and activity is contagious amongst the children, who want

to manipulate the concrete materials with their hands and other senses.

“The environment

must be a living one, directed by a higher intelligence, arranged by an adult

who is prepared for his mission.” – Maria Montessori

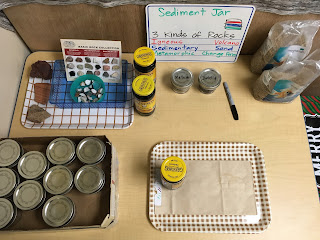

The center of the 6-9 year old mixed-age classroom is Cosmic Education, the

scope and order of the stories of the Universe from largest and oldest to the

most recent and familiar. The vastness of the Cosmic curriculum in particular –

from astronomy, physics, and chemistry to geology, geography, and life sciences

– demands fluidity of movement as the children move through the Great Lessons. The

children’s best and first teacher is the real material which they are given to

touch, such as real plants in need of water, real fossils of trilobites, and

real igneous rock that was once ejected from a real volcano.

“The child must live in an

environment of beauty.” – Maria Montessori

Regular change on the Cultural

shelves mimics the inevitable and continuous changes on Earth – from the growth

of continental plates from vulcanism to the erosion of rock through the Work of

Wind and the Work of Water to the migration of humans due to natural hazards

and civilization. These grand ideas are presented as key experiences to spark

the imagination of the child.

“To do well, it is

necessary to aim at giving the elementary age child an idea of all fields of

study, not in precise detail, but an impression. The idea is to sow the seeds

of knowledge at this age, when a sort of sensitive period for the imagination

exists.” – Maria Montessori

Math shelves contain materials which

the child can use independently or with a partner after an initial lesson from

an adult Montessori guide. The materials are also sequential and attuned to

different learning styles. For example, several different materials can be used

by a child learning a math operation, such as addition. The Golden Beads are

all the same color and require the child to use her pincer grip, which is

developing at the 6-9 ages, with great care and precision. The Stamp Game is

similar to the Golden Beads in terms of quantity and place value concepts, yet

variations include size, shape, and color (also reinforcing place value – green

representing units, blue representing tens, and red representing hundreds).

“The first aim of

the prepared environment is, as far as it is possible, to render the growing

child independent of the adult.” – Maria Montessori

The Small and Large Bead Frames are

often an option preferred by children with strong spatial and kinesthetic

learning styles, especially those who have tired of using the Stamp Game in a

plane; the Bead Frames allow exchanging to happen in the vertical sphere. The

Bank Game allows children to work together in small groups, role-playing using

the expanded form of the operations. In most Montessori classes, the children

eventually (and ideally) work with such confidence and independence that they

hardly register the observing presence of their adult guide.

“The teacher’s

first duty is to watch over the environment, and this takes precedence over all

the rest. Its influence is indirect, but unless it is well done there

will be no effective and permanent results of any kind; physical, intellectual

or spiritual.” – Maria Montessori

Language shelves contain materials

(usually card materials) which are self-correcting and self-explanatory for a

child to use – again, after an initial lesson with an adult Montessori guide,

by herself or with a partner. Children learn sounds of vowels and consonants

using Phonics towers, language relationships (such as compound words, synonyms,

and homophones) using Word Study drawers, and parts of speech (such as nouns,

adjectives, and prepositions) using Grammar boxes.

“Not upon the

ability of the teacher does education rest, but upon the didactic system.

When the control and correction of errors is yielded to the materials, there

remains for the teacher nothing but to observe.” – Maria Montessori

Children keep track of the drawers

they complete in order to find appropriate partners of any age, and many

children enjoy the maturity and responsibility of giving lessons to their

peers. The adult guide watches and intervenes only when needed, redirecting the

child back to the material and using questions to assist in the child’s own

discovery. Children help each other in the same way as the adult models them,

avoiding telling an answer and instead asking questions or walking through the

prepared environment to locate resources such as a dictionary, atlas, or

thesaurus.

“Education is a

natural process carried out by the human individual, and is acquired not by

listening to words, but by experiences in the environment.” – Maria Montessori

Practical Life is an area of the

Montessori curriculum which is central to the 3-6 year-old Primary classroom,

however since Lower Elementary children ages 6-9 are also still developing fine

motor, gross motor, sensory integration, and self-regulation skills, the

activities and materials on the Practical Life shelves provide great relief and

reprieve for children from the abundant (and sometimes rigorous) academic

materials.

“The exercises of

practical life are formative activities, a work of adaptation to the

environment. Such adaptation to the environment and efficient functioning

therein is the very essence of a useful education.” – Maria Montessori

Practical Life materials are hands-on

– such as braiding, sorting, and weaving. Practical Life materials are creative

– such as watercolors, clay tablets, and building blocks. Practical Life

materials soothe and calm the whole body – such as yoga, jumping rope, and

carrying hand weights. These shelves are favorites for children in need of a “brain

break” who often return to their intellectual work soon after with renewed

energy and concentration.

“The materials, in

fact, do not offer to the child the content of the mind, but the order for that

content.” – Maria Montessori

One of the most iconic places in any

Montessori learning environment is the Peace Table, a beautiful space where

children may sit by themselves or with a friend with whom they have conflict.

In a Primary room, a single rose in a vase on a table symbolizes Peace. In my

Lower Elementary classroom, I have decorated our Peace Table (which sits close

to the floor) with a soft scarf, a Tibetan singing bowl, a Chinese meditation

egg, and a few lovely gemstones. Maria Montessori respected children as emotional,

intellectual, social beings. The adult guide may give a lesson on how to use

the Peace Table – either for internal balance or for interpersonal

problem-solving – yet it remains in the child’s power to decide if and when to

use the materials.

“The children must

be free to choose their own occupations, just as they must never be interrupted

in their spontaneous activity.” – Maria Montessori

The scope and sequence of the

Montessori curriculum and classroom set-up is quite intentional, not unlike the

scaffolding of a building under construction – or a theater stage. Children are

unaware of the preparation of their learning environment – from lessons to

materials to shelf layout and rotation. They do not need to know all the

content or all the steps in order to grow. They only need to feel secure that

they are free to explore and discover in an organized fashion.

“Freedom without

organization is useless. The organization of the work, therefore, is the

cornerstone of this new structure. But even that organization would be in

vain without the liberty to make use of it.” – Maria Montessori