In reading Alfie Kohn's 2005 book Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishments to Love and Reason, some passages have given me pause to reflect:

"We might say that discipline doesn't always help kids to become self-disciplined... There's a big difference, after all, between a child who does something because he or she believes it's the right thing to do and one who does it out of a sense of compulsion... if we place a premium on obedience at home, we may end up producing kids who go along with what they're told to do by people outside the home, too." (pp. 6-7)

Kohn discusses BF Skinner and Behaviorism, a tendency to focus solely on actions and not on the feelings nor thoughts behind them. Montessori philosophy encourages self-discipline. Teachers act as guides, respecting the child through use of inquiry in three-part lessons and discussion in groups. Students engage with questions rather than parrot anticipated answers. Through problem-solving and reading literature related to social skills, students give suggestions for finding peaceful solutions to problems. It is often helpful to ask a child a question and let him/her find an answer rather than making unsolicited demands or nagging.

"Perhaps you've met (adults) who force ... children to apologize after doing something hurtful or mean... So (they) assume that making children speak this sentence will magically produce in them the feeling of being sorry, despite all evidence to the contrary?... Compulsory apologies mostly train children to say things they don't mean -- that is, to lie." (p. 14)

A few years ago, a precocious student had a rough time respecting my assistant. I spoke with the child after an unpleasant event between them and listened to his side of the story. I then tried to facilitate peace by asking him to apologize to my assistant, either in verbal or written form. He said that he could apologize to her, but he wouldn't mean it. I asked if he could consider ways in which he could be more respectful to her, instead. He came up with many ideas, none of which involved pretending he was sorry when he wasn't.

Kohn quotes noted psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci (also quoted by Daniel Pink in Drive) asserting that "children are born not only with certain basic needs, including a need to have some say over their own lives, but also with the ability to make decisions in a way that meets their needs", what Ryan and Deci term "a gyroscope of natural self regulation" which can be undermined by guilt, needless interference, physical force, criticism, and even praise: "a heavy handed (adult) does nothing to promote, and actually may undermine, children's moral development. Those who are pressured to do as they're told are unlikely to think through ethical dilemmas for themselves" (pp. 58-59). Lack of self-regulation also impacts, Kohn observes, personal health choices, social relations, interests, commitments, and acquisition of learning. Alternatives are for adults to exercise restraint in interactions with children, remember to respect children as people, ask questions rather than make assumptions, separate emotional reactions from the child's will, and say "I notice" when observing behaviors rather than ascribing a positive or negative judgment.

One of the contentious suggestions that Kohn makes in this book and some of his others is that grading negatively impacts students. He cites studies that demonstrate this and claims that "the more a child is thinking about grades, the more likely it is that his or her natural curiosity about the world will start to evaporate" (p. 80).

After hearing Kohn speak last fall, I shared some of his ideas with the students in my class at a class meeting, a democratic gathering where topics and suggestions are discussed. I had noticed that when math fact and spelling tests were handed back for correction with a numeric grade on the paper, students compared themselves to one another, some bragging and some feeling disappointed in their abilities. Some adults feel that competition is a natural part of life "in the real world" that children will eventually have to face, and while I agree with that unfortunate fact, I do not feel that grades as such need to be transparent to students. I suggested a trial period where grades would be recorded by me but not shown on the paper, only the grammatical and mechanical corrections. That was six months ago, and no one has complained about their absence. In fact, I have noticed that students are less self-aware and more confident when given these protective options. Our school reports S and S+ "marks" at the 6-9 level with extensive narrative descriptions that many contemporary education researchers advocate, as well.

Kohn offers some guiding principles for expressing unconditional love by avoiding rewards and punishments, which include keeping your eye on long-term goals, talking less and asking more, attributing to children the best possible motive consistent with the facts, saying yes more than saying no, and avoiding rigidity and hurrying a child according to your needs (p. 119-120). Sometimes, we adults who have become accustomed to our own schedules expect the world to know our timetable and are flummoxed when traffic does not stop for us. Plan ahead and know your child so that you can help him/her instead of asking for frequent adaptation to your expectations. This means avoiding over-planning and making sure, whenever possible, that your child's needs come first. For example, a child told me recently that he hadn't slept well the night before, and the reason he was late to school was that his mom let him sleep in so he would be alert. I applaud this parent for thinking of her child's needs. One of the most salient suggestions Kohn offers are three questions for adults to ask themselves regarding their speech and actions with children (and it also applies to our interactions with adults): why am I asking this, is it necessary, and how will the other person receive it (p. 158-160)?

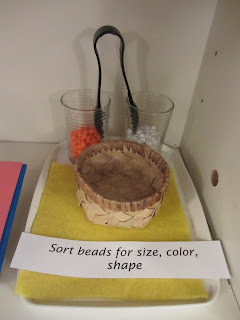

Montessori education -- which provides a prepared, sequential, and orderly scope and sequence of curriculum -- gives students a range of choices for their auto-education. We guides give lessons, yet much of the learning that happens in our classrooms occurs through the materials teaching the students as frequently as needed for absorption and as rarely as needed after abstraction. Materials make great guides, because they do not praise nor punish, but simply offer a control of error, another of Maria Montessori's amazing insights over a century ago. Autonomy does not mean independence but volition, and children are more willing and eager in situations where they feel they have choice.

As Kohn notes, "when teachers give their students more choice about what they're doing... the advantages include greater perceived competence, higher intrinsic motivation, more positive emotionality, enhanced creativity, a preference for optimal challenge over easy success, greater persistence in school, greater conceptual understanding, and better academic performance" (p. 169). That is, after all, what every teacher wants for her students, what every parent wants for his child, and what every student wants for him/herself.