“What

the hand does, the mind remembers.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

Children

remind me that they learn with their hands, something Dr. Montessori understood

through quiet observation over a century ago. This continues to be true in the

current time of digital technology (literally: tools used by the hands) and an

adult focus on abstraction as a metric of success. I have grappled with the

inclusion of technology and testing in the Montessori classroom, in both

private and public charter environments, and I continue to believe that they

are incongruous with the beautiful and patient process of a child learning by

holding actual objects – clay, fossils, fern fronds – with their hands.

“Do

not tell them how to do it. Show them how to do it and do not say a word. If

you tell them, they will watch your lips move. If you show them, they will want

to do it themselves.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

A few years ago, I asked a mother of one of my students to come in

and demonstrate how she makes her own kombucha. There were simple ingredients

and a live bacteria, which we stored in our room for weeks and watched grow,

documenting its bubbling surface and the layers that it formed in a controlled

environment. It is much easier to just buy a bottle of kombucha at a store,

however the children looked forward to being a part of the process – using gloves

to touch the SCOBY, selecting the flavors to add. Convenience is not always

possible nor preferable. It often stalls understanding.

"The senses, being explorers of the world, open the way to

knowledge." –

Dr. Maria Montessori

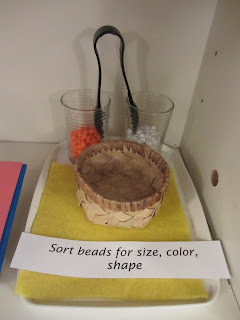

In the Montessori learning environment, especially the expansive

Cosmic Curriculum, there are many varieties of concrete materials – from the

wooden Bohr diagram modeling the inside of an atom to the Timeline of Life with

era boxes full of fossils to the Land and Water forms (used with colored water

poured from a jug). Many of these initial materials have extensions which allow

interested children to go deeper. For example, many children choose to make

their own Land and Water booklet with brown and blue paper, or (in this case,

shown above) models formed by painting dried clay models.

When I think about the ways in which public education (and, often,

adult thinking in general) prioritizes large quantities of superficial, one-time-only

lessons – some of which are never reviewed nor returned to – I feel thankful

that Montessori education functions in the exact opposite manner. Children are

encouraged to go deeper, to be reiterative, to be creative with a concept,

making the trench of the neural pathways surrounding it that much further

ingrained.

“Education

is a natural process carried out by the child and is not acquired by listening

to words but by experiences in the environment.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

Children

learn about Parts and Kinds in Montessori education, from math to language to

science:

Parts of the Atom and Kinds of Atoms

Parts of a Line and Kinds of

Lines

Parts of Speech and Kinds of Words

Children are attracted to the

largest things and the smallest things. When we study the Coming of the Earth,

we find an inter-relatedness with the Inner Earth and the Plate Tectonic

activity that caused and causes land forms to exist, that allowed animal and

eventually human migration to occur. Children are fascinated by superlatives:

the highest, the furthest, the smallest, the coldest, the hottest. Again, it

would be easier to simply purchase a model of a volcano from a craft store.

However, witness these children forming volcanoes with their own hands!

“The

hands are the instruments of man’s intelligence.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

It

is amazing to be alive, and children in Lower Elementary also come to a

knowledge that death is something that belongs to all things. We study life

cycles of living things, such as a tree or a jellyfish, and we also know where

our Universe is in its own lifespan. (Like me, it’s middle-aged!) This knowledge

of the ephemeral quality of nature is deepened when children see the Timeline

of Life, specifically how old the world is, how old other organisms are (like

the jellyfish, one of the longest lived creatures on the planet), and how young

we humans are as a species. When we study the life cycle, we see the same

phases and know that each organism is unique and special.

“The

human hand allows the mind to reveal itself.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

One

of the most inspiring things to see is what children create from their own

imaginations. When they use geometric building blocks as a Practical Life

activity, they are resting their reading mind and engaging their body – their kinesthetic

and tactile intelligences. They are using the concept of gravity when they

balance an arch on a cone. They are using the concept of symmetry when they build

a structure out of rectangular prisms, pyramids, and cylinders. Mainly, though,

they are free to experiment, make mistakes, try again, and eventually hopefully

innovate while creating an architecture of their own happiness.